While there are a number of feature films in which photography or photographers play a part (Rear Window, The Year of Living Dangerously, The Eyes Of Laura Mars and Salvador, for example) those which explore the nature of the medium itself are rare. Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966) considers photography as part of the fashion scene, but then sees photographer Thomas (David Hemmings) accidentally photographing a murder—photography becomes the inadvertent witness to events not even seen by the photographer. Jocelyn’s Moore’s Proof (1991) sees Hugo Weaving playing a blind photographer, who uses a camera as his eyes, to make images which for him constitute ‘proof’ that the visible world is as he perceives it to be through his other senses. In Wayne Wang’s film Smoke (1995) photography is a literal capture device, capable of incarcerating the subject as well as the photographer.

Auggie Wren (Harvey Keitel) owns the ‘Brooklyn Cigar Company’, a small business selling cigarettes and cigars at the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue, New York. His friends, regulars who frequent his shop, know Wren as a shop-owner, but they do not know of his secret—he is a photographer. How he came to own his camera is the basis of a story the he tells to a regular customer, Paul Benjamin (William Hurt).[1]

Benjamin is a writer, and arrives at the shop late one evening to find Wren locking up. He hopes to purchase a box of his favourite Schimmelpenninck miniature cigars and Wren re-opens the shop for him. After the transaction and some small-talk Benjamin notices a camera, a Canon 35mm SLR, amid the smoking products and paraphernalia on the counter.

BENJAMIN: Looks like someone forgot a camera.

WREN: Yeah, I did.

BENJAMIN: It’s yours?

WREN: It’s mine alright. I’ve owned that little sucker for a long time.

BENJAMIN: I didn’t know you took pictures.

WREN: I guess you could call it a hobby. It only takes five minutes a day to do it but I do it every day, rain or shine, sleet or snow. Like the postman.

BENJAMIN: So you’re not just some guy who pushes coins across the counter?

WREN: Well, that’s what people see, but that ain’t necessarily what I am.

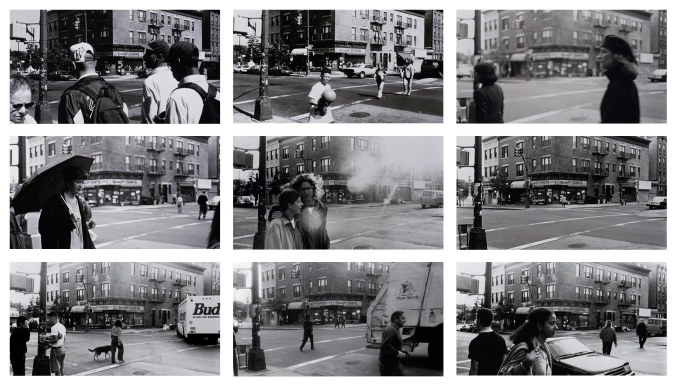

Cut to album of black and white photographs. A page of 4—all showing the outside of the Brooklyn Cigar Company, the shop owned by WREN

BENJAMIN: (leafing through the album) They’re all the same.

WREN: That’s right. More than four thousand pictures of the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue at eight o’clock in the morning, four thousand straight days in all kinds of weather. That’s why I can never take a vacation. I got to be in my spot every morning at the same time … every morning in the same spot at the same time.

BENJAMIN: I’ve never seen anything like this.

WREN: That’s my project. What you’d call my life’s work.

BENJAMIN: It’s amazing. I’m not sure I get it though. I mean … What was it that gave you the ideas to do this … project?

WREN: I don’t know, it just came to me. It’s my corner after all. I mean, it’s just one little part of the world but things take place there, too, just like everywhere else. It’s a record of my little spot.

BENJAMIN: It’s kind of overwhelming.

BENJAMIN leafs through the album, flicking fast.

WREN: You’ll never get it if you don’t slow down, my friend.

BENJAMIN: What do you mean?

WREN: Well. You’re going too fast. You’re hardly even looking at the pictures.

BENJAMIN: But … they’re all the same.

WREN: They’re all the same, but each one is different from every other one. You’ve got your bright mornings; your fog mornings; you’ve got your summer light and your autumn light; you’ve got your week days and your weekends; you’ve got your people in overcoats and galoshes and you’ve got your people in t-shirts and shorts. Sometimes same people, sometimes different ones. Sometimes different ones become the same, and the same ones disappear. The earth revolves around the sun and every day the light from the sun hits the earth from a different angle.

BENJAMIN: Slow down, huh?

WREN: That’s what I recommend. You know it: tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. Time keeps its petty pace.

BENJAMIN leafs slowly, recognises a face: his wife, who was shot and killed in a bank hold-up a few years earlier.

BENJAMIN: Oh, Jesus! Look! It’s Ellen …

WREN: Yeah, it’s her alright. She’s in quite a few from that year. Must’ve been on her way to work.

BENJAMIN: It’s Ellen. Look at her. Look at my sweet darling. (He breaks down and cries.)

End of scene.

This exchange tells us much about the nature of photography: its power to transform, to captivate, to illuminate, to remember, to imprison.

In Benjamin’s eyes—and Benjamin is a writer and therefore an artist, too, a published novelist—the act of photography raises Wren’s status from that of a shop keeper, a small businessman, into the realms of art. Just owning the camera is enough: Benjamin arrives at his conclusion before seeing any of Wren’s photographs. Ownership of the camera confers a status of the ‘other’, of a power which transforms Wren, making him instantly more interesting without requiring him to do anything else.

Once Benjamin looks at the photographs he is captivated, not only by the repetition but by Wren’s insistence that the apparent sameness is superficial; that there is a depth to the images which remains unseen and misunderstood if we do not linger over them, to engage with them and ‘get to know’ them. Listening to Wren’s explanation of the nuanced differences we, the viewers, become captivated by the images, too. But more importantly, we are gripped by the idea that interesting things can happen in our little corner of the world, as well. All it needs is for us to look, and to see.

The place that Wren photographed is a local corner, important to him because it is where his business is. Taking his photographs he becomes a part of the corner, and his subjects stop taking any notice of the photographer. His invisibility is what lends a truth to the images; not a ‘scientific’ truth but a subjective truth of an acute observer engaged with the world that he knows. By becoming invisible himself he is able to make the mundane visible. One is reminded of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who painted his silver Leica black and who refused to allow his own photograph to be published because he wished to remain anonymous on the streets of Paris, to be able to take photographs unseen by those at whom he was looking. And so it is, often, with photography—the photographer becomes invisible, an unseen stalker on city streets.

Unbeknown to Benjamin when he sits down to look at the photographs is that he has a personal interest in the images, in the likeness of his wife who is lost to him in reality but is still there, trapped in the black-and-white pictures the Wren has placed so carefully in albums.

But in an ironic twist, just as the camera captures the images of the people in the street—has captured Benjamin’s wife, now dead—Wren is also captured. In the process of recording the people who pass by his lens he is ensnared: his habit has become an obsession. He now must record the scene at 8.00 a.m. each day, must ‘…be in my spot every morning at the same time … every morning in the same spot at the same time.’ There is no reason for this other than one of his own making. Now, however, he finds that he can now no even have a holiday because there would be no one to take the photograph.

Like the subjects of his photographs Wren is himself imprisoned by his obsession, and the longer he pursues it the harder it is for him to break free.

Some of Auggie Wren’s images from ‘Smoke’, 1995. (Still Photographer K.C. Bailey.)

Some of Auggie Wren’s images from ‘Smoke’, 1995. (Still Photographer K.C. Bailey.)

Text © Stuart Peel 2013

[1] The film is based on a short story, ‘Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story’, by American writer Paul Auster, and the character of Benjamin is based on Auster himself. The original short story was published in the New York Times at Christmas 1990, and is related in the film by Harvey Keitel. The complete short story can be downloaded from http://www.xtec.cat/~dsanz4/materiales/auggie_wren.pdf

Well, thanks Stuart for noticing. For the record, the entire photo series was staged over the course of three days. We used friends and family for the photos, and “Ellen” was played by one of our crew from the art dept. Wayne is a joy to work for and Paul Auster was standing by my side when we shot it. Best, K C Bailey

Hi KC. I really didn’t expect to hear from the photographer! The film has been a favourite of mine for quite some time, and I was moved to write this after re-watching it with my 18-year-old son, who loved it too. It is a great example of what film-making can do–you don’t need car chases, explosions and helicopters to make an intelligent, thoughtful and entertaining film. Stuart

Dear KC,

I live across the street from the fictional smoke shop. How can I get a print of one of your photos?